BRICS Expansion and the Shifting Global Order

As more big emerging markets join the BRICS+ nations, the grouping could give the Global South a greater voice in world affairs and challenge the domination of existing institutions.

Lisa Ivers

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Head of Africa | Boston Consulting Group

The ten BRICS+ nations account for half the world’s population and two-fifth of trade—and include major energy producers and importers. Twelve more nations have applied.

The bloc is starting to build institutions with important implications for energy trade, international finance, supply chains, and technological research.

Global companies will need to factor geopolitics into their investment strategies and strengthen their capacity to capture the opportunities and mitigate the risks of BRICS expansion.

As attention focuses on wars in Eastern Europe and the Middle East and mounting tensions between the world’s great powers, a structural shift in the global order has been quietly underway. Large developing nations are exerting greater influence in world economic affairs and are beginning to build alternatives to Western-led institutions.

At this movement’s core is a formal intergovernmental grouping known as the BRICS+. The grouping includes five longstanding members—Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa—as well as five that joined in January 2024 or have been invited: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Together, these ten nations account for around 40% of both crude oil production and exports. They also account for one-quarter of global GDP, two-fifths of global trade in goods, and nearly half of the world’s population. Adding another dozen nations that have applied for membership, including dynamic emerging markets such as Thailand, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, would raise the group’s share to one-third of global GDP.

A larger BRICS challenges the dominance of existing global institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, that are strongly influenced by the West. It also further weakens the relevance of the G-20, a grouping founded in 1999 to seek economic policy alignment among the largest industrialised and developing economies. Indeed, the G20 is fraying at both ends: its seven most economically advanced members are strengthening their ties through the G7, while its six large developing economies are asserting their own voices within BRICS+.

BRICS+ creates a forum that, at minimum, gives emerging markets the opportunity to align on global topics and new opportunities to promote mutual economic development and growth. And it’s evolving steadily. As it begins building political and financial institutions and a payment mechanism for executing transactions, there are important potential implications for the future of energy trade, international finance, global supply chains, monetary policy, and technological research. As a result, global companies will need to factor these new geopolitical and economic realities into their investment strategies. They should also strengthen their capacity to capture the opportunities and to mitigate risk that they engender.

How BRICS+ has evolved

Leaders of the original BRICS nations held their first summit in 2009 to discuss reforming international financial institutions, which they believed did not adequately address the interests of the Global South. Aside from the United Nations and G20, which included all five BRICS, there was no major forum where emerging markets could discuss their own economic and geopolitical agendas. Development assistance and funding for infrastructure through financial institutions established largely by Western powers after World War II often came with challenging strings attached.

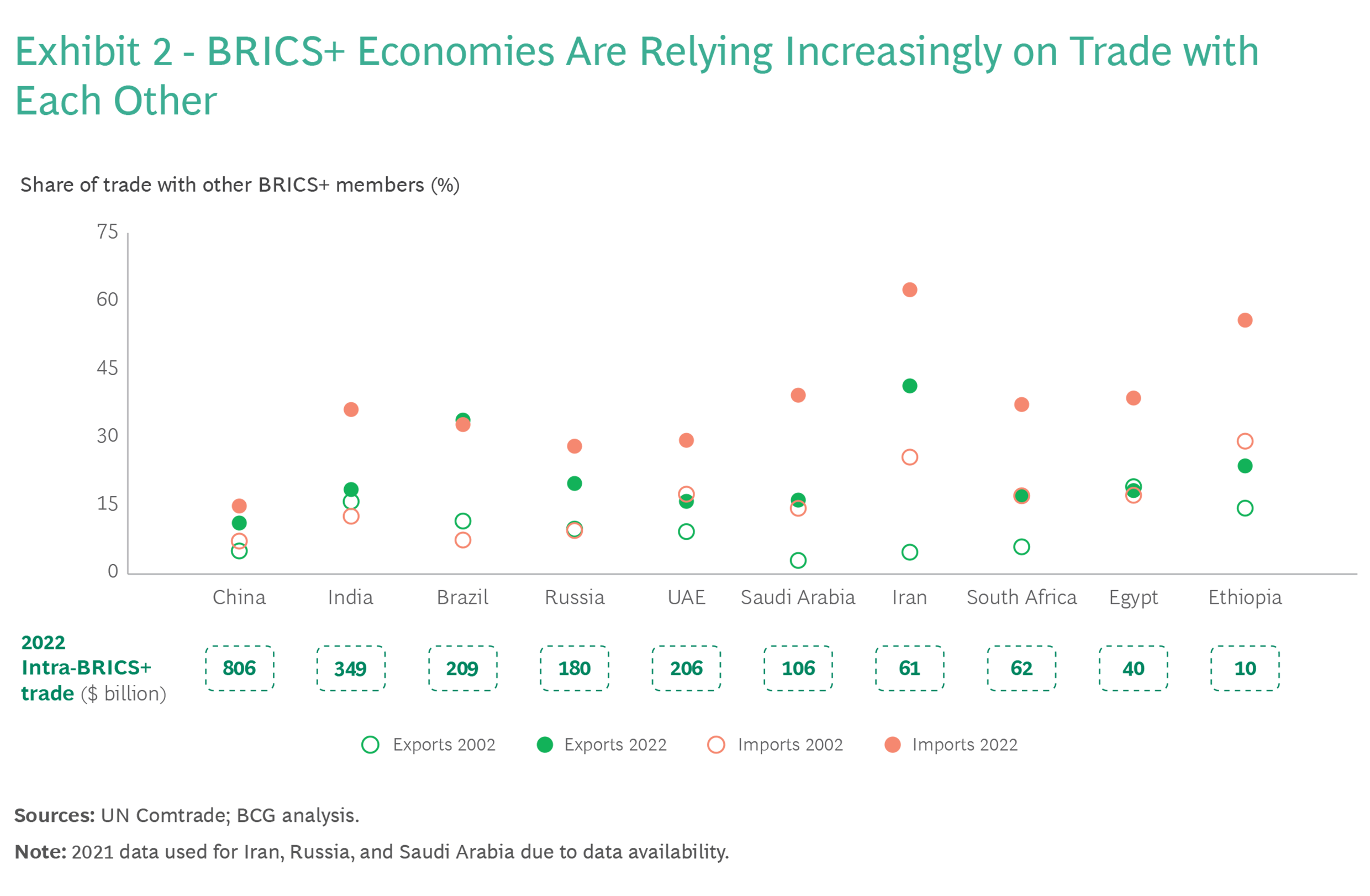

There has been scepticism from the beginning over whether BRICs would evolve into a functioning bloc. But over the years, these nations have been drawing nearer to each other economically. Trade in goods among BRICS economies has considerably outpaced trade between the BRICS and G7 nations, leading to greater intra-BRICS trade intensity.

Decades of rapid growth have also given many of these economies far more weight in the global economy, both as producers and consumers. (Exhibit 3.) Because many of these nations are engaged with both advanced economies and China, which is perceived as an economic and trade superpower, they can create another coalition less dependent on the West.

Recent crises have added momentum to BRICS expansion. Several big developing nations that are aligned with neither NATO nor Russia resisted pressure to adhere to Western-imposed sanctions on Moscow in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Others have complained that G7 nations’ initiatives to combat climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic did not take their needs into account. BRICS+ institutions have been slowly evolving through regular meetings, joint initiatives, and formal bodies.

Yet grounds for scepticism over BRICS+’s capacity to become an effective institution remain. This grouping includes countries that are very diverse in terms of political systems, institutional frameworks, economic models, and cultural backgrounds. It even includes geopolitical rivals; for example, relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as between China and India, remain strained. A so-called “China shock” of low-cost exports of everything from steel and chemicals to machinery could also raise trade tensions within the group. The expansion, moreover, is heavily tilted toward the Middle East, so further regional balance may be required as the group grows.

The impact for Africa

Shifting the view to the African continent, Lisa Ivers, Head of Africa for Boston Consulting Group (BCG), shares her observations stating, “The current ‘tectonic shifts’ create a unique opportunity for Africa to reposition itself in the new trade order. Many African countries could benefit from nearshoring or China+1 strategies, especially those North African countries supplying Europe in sectors such as automotive, textile or agribusiness.”

“Everybody’s fighting for critical minerals for the energy transition. Being home to abundant resources like cobalt, copper, manganese or rare earth, there is a momentum for Sub-Saharan Africa to reinvent its position on mining and transformation value chains and reshape its relationship to the Western world.”

“Once fully outbound oriented, we are seeing more and more how Africa is growing its internal trade and tourism. The implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a continent-wide free trade area, is an ambitious initiative aiming at fostering intra-Africa trade flows, reducing dependency, and creating more growth for the continent.”

This is aligned to the fact that BRICS+ markets are likely to experience significant growth over the next decade. While the group lacks formal trade and investment agreements, it already has substantial, growing intra-BRICS trade. BRICS+ markets could become valuable gateways for companies seeking to expand to other emerging markets. The success of China-made EVs in BRICS+ markets is a good example of how companies can customise offerings to reach consumers across the member countries.

As much as there is opportunity, an expanded BRICS does present risks for business. Companies should anticipate that BRICS+ will develop more formal institutions and agreements in the years ahead and begin planning for such scenarios with bespoke action to be considered in five key areas - developing a BRICS-for-BRICS go-to-market strategy; leveraging on the anticipated infrastructure boom; refining risk and compliance; adapting the China + 1 strategy in consideration of building supply chains that can leverage the BRICS+ economies and building geopolitical sensing capabilities across their business units, functions, and regional managements to balance business efficiency with risk mitigation.

Recent years of new geopolitical tensions, economic ambition and instability, trade wars, and a pandemic have clearly brought lasting, structural change and challenges to the business landscape we once knew. The growth of the BRICS+ shows that, after decades of strong economic development, emerging markets are now ready for a larger role in the world order, one that better reflects their interests. Companies that adapt to this movement will be more likely to thrive in an evolving era of multipolar competition.

Ends